824 F.3d 871 (9th Cir. 2016)

Complaining Work |

Defending Work |

|

Vincent Montana, Richard Pettibone “Chicago Bus Stop (Ooh, I Love It) (Love Break)” |

Madonna Ciccone, Richard Pettibone. “Vogue” |

Comment by Bradley Ryba

The plaintiff Salsoul sued Madonna and her producer for an allegedly unlicensed sample of a horn hit from Salsoul’s song “Love Break.” Despite Salsoul’s certificate of copyright registration, the court found that Salsoul did not have a protectable copyright interest because the horn hit was not sufficiently original.

Regarding the originality necessary to be a copyrighted element of the musical composition, the court first noted that the horn hit, which was transcribed in four measures, was a single chord consisting of four notes. Sequences of less than six notes are generally not distinct enough for copyright protection absent other circumstances (e.g. presence of accompanying lyrics, sequences at the heart of the compositions, repetitive sequences and lyrics, or sequences based upon analyses of both the written composition and the sound recording). Because those circumstances were not present, the horn hit was not sufficiently unique for protection as an element of the musical composition.

Concerning the originality necessary to be a copyrighted element of the sound recording, the court found that “playing horns in a percussive manner was a common practice” that defeated Salsoul’s claim for originality as to that playing style. As such, Salsoul did not have any copyright protection in the horn hit.

For good measure, the court noted that any potential copying would be de minimis.

In June, 2016 the 9th Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment to the defendants, but it also vacated the lower court’s awarding defendants attorney fees. The 9th Circuit’s Judge Silverman dissented from the majority’s opinion, and criticizes what he perceives as its baseless rejection of the 6th Circuit’s “bright line” rule governing sampling.

9th Cir. Opinion by Judge Graber

Copy of opinion 834 F. 3d 871 (9th Cir. 2016): PDF

In the early 1990s, pop star Madonna Louise Ciccone, commonly known by her first name only, released the song Vogue to great commercial success. In this copyright infringement action, Plaintiff VMG Salsoul, LLC, alleges that the producer of Vogue, Shep Pettibone, copied a 0.23-second segment of horns from an earlier song, known as Love Break, and used a modified version of that snippet when recording Vogue. Plaintiff asserts that Defendants Madonna, Pettibone, and others thereby violated Plaintiff’s copyrights to Love Break. The district court applied the longstanding legal rule that “de minimis” copying does not constitute infringement and held that, even if Plaintiff proved its allegations of actual copying, the claim failed because the copying (if it occurred) was trivial. The district court granted summary judgment to Defendants and awarded them attorney’s fees under 17 U.S.C. § 505. Plaintiff timely appeals.

Reviewing the summary judgment de novo, Alcantar v. Hobart Serv., 800 F.3d 1047, 1051 (9th Cir. 2015), we agree with the district court that, as a matter of law, a general audience would not recognize the brief snippet in Vogue as originating from Love Break. We also reject Plaintiff’s argument that Congress eliminated the “de minimis” exception to claims alleging infringement of a sound recording. We recognize that the Sixth Circuit held to the contrary in Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films, 410 F.3d 792 (6th Cir. 2005), but—like the leading copyright treatise and several district courts—we find Bridgeport’s reasoning unpersuasive. We hold that the “de minimis” exception applies to infringement actions concerning copyrighted sound recordings, just as it applies to all other copyright infringement actions. Accordingly, we affirm the summary judgment in favor of Defendants.

But we conclude that the district court abused its discretion in granting attorney’s fees to Defendants under 17 U.S.C. § 505. See Seltzer v. Green Day, Inc., 725 F.3d 1170, 1180 (9th Cir. 2013) (holding that we review for abuse of discretion the district court’s award of attorney’s fees under § 505). A claim premised on a legal theory adopted by the only circuit court to have addressed the issue is, as a matter of law, objectively reasonable. The district court’s conclusion to the contrary constitutes legal error. We therefore vacate the award of fees and remand for reconsideration.

FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Because this case comes to us on appeal from a grant of summary judgment to Defendants, we recount the facts in the light most favorable to Plaintiff. Alcantar, 800 F.3d at 1051.

In the early 1980s, Pettibone recorded the song Ooh I Love It (Love Break), which we refer to as Love Break. In 1990, Madonna and Pettibone recorded the song Vogue, which would become a mega-hit dance song after its release on Madonna’s albums. Plaintiff alleges that, when recording Vogue, Pettibone “sampled” certain sounds from the recording of Love Break and added those sounds to Vogue. “Sampling” in this context means the actual physical copying of sounds from an existing recording for use in a new recording, even if accomplished with slight modifications such as changes to pitch or tempo. See Newton v. Diamond, 388 F.3d 1189, 1192 (9th Cir. 2004) (discussing the term “sampling”).

Plaintiff asserts that it holds copyrights to the composition and to the sound recording of Love Break. Plaintiff argues that, because Vogue contains sampled material from Love Break, Defendants have violated both copyrights. Although Plaintiff originally asserted improper sampling of strings, vocals, congas, “vibraslap,” and horns from Love Break as well as another song, Plaintiff now asserts a sole theory of infringement: When creating two commercial versions of Vogue, Pettibone sampled a “horn hit”1 from Love Break, violating Plaintiff’s copyrights to both the composition and the sound recording of Love Break.

The horn hit appears in Love Break in two forms. A “single” horn hit in Love Break consists of a quarter-note chord comprised of four notes—E-flat, A, D, and F—in the key of B-flat. The single horn hit lasts for 0.23 seconds. A “double” horn hit in Love Break consists of an eighth-note chord of those same notes, followed immediately by a quarter-note chord of the same notes. Plaintiff’s expert identified the instruments as “predominantly” trombones and trumpets.

The alleged source of the sampling is the “instrumental” version of Love Break,2 which lasts 7 minutes and 46 seconds. The single horn hit occurs 27 times, and the double horn hit occurs 23 times. The horn hits occur at intervals of approximately 2 to 4 seconds in two different segments: between 3:11 and 4:38, and from 7:01 to the end, at 7:46. The general pattern is single-double repeated, double-single repeated, single-single-double repeated, and double-single repeated. Many other instruments are playing at the same time as the horns.

The horn hit in Vogue appears in the same two forms as in Love Break: single and double. A “single” horn hit in Vogue consists of a quarter-note chord comprised of four notes—E, A-sharp, D-sharp, and F-sharp—in the key of B-natural.3 A double horn hit in Vogue consists of an eighth-note chord of those same notes, followed immediately by a quarter-note chord of the same notes.

The two commercial versions of Vogue that Plaintiff challenges are known as the “radio edit” version and the “compilation” version. The radio edit version of Vogue lasts 4 minutes and 53 seconds. The single horn hit occurs once,4 the double horn hit occurs three times, and a “breakdown” version of the horn hit occurs once. They occur at 0:56, 1:02, 3:41, 4:05, and 4:18. The pattern is single-double-double-double-breakdown. As with Love Break, many other instruments are playing at the same time as the horns.

The compilation version of Vogue lasts 5 minutes and 17 seconds. The single horn hit occurs once, and the double horn hit occurs five times. They occur at 1:14, 1:20, 3:59, 4:24, 4:40, and 4:57. The pattern is single-double-double-double-double-double. Again, many other instruments are playing as well.

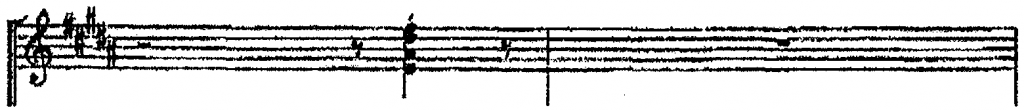

One of Plaintiff’s experts transcribed the composition of the horn hits in the two songs as follows. Love Break’s single horn hit:

Vogue’s single horn hit:

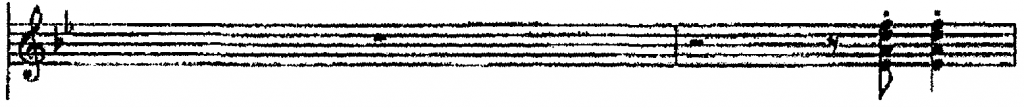

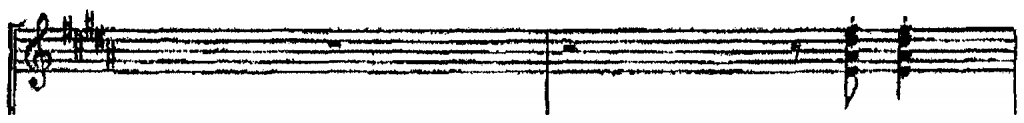

Love Break’s double horn hit:

Vogue’s double horn hit:

In a written order, the district court granted summary judgment to Defendants on two alternative grounds. First, neither the composition nor the sound recording of the horn hit was “original” for purposes of copyright law. Second, the court ruled that, even if the horn hit was original, any sampling of the horn hit was “de minimis or trivial.” In a separate order, the district court awarded attorney’s fees to Defendants under 17 U.S.C. § 505. Plaintiff timely appeals both orders.

DISCUSSION

Plaintiff has submitted evidence of actual copying. In particular, Tony Shimkin has sworn that he, as Pettibone’s personal assistant, helped with the creation of Vogue and that, in Shimkin’s presence, Pettibone directed an engineer to introduce sounds from Love Break into the recording of Vogue. Additionally, Plaintiff submitted reports from music experts who concluded that the horn hits in Vogue were sampled from Love Break. Defendants do not concede that sampling occurred, and they have introduced much evidence to the contrary.5 But for purposes of summary judgment, Plaintiff has introduced sufficient evidence (including direct evidence) to create a genuine issue of material fact as to whether copying in fact occurred. Taking the facts in the light most favorable to Plaintiff, Plaintiff has demonstrated actual copying. Accordingly, our analysis proceeds to the next step.

Our leading authority on actual copying is Newton, 388 F.3d 1189. We explained in Newton that proof of actual copying is insufficient to establish copyright infringement:

For an unauthorized use of a copyrighted work to be actionable, the use must be significant enough to constitute infringement. See Ringgold v. Black Entm’t Television, Inc., 126 F.3d 70, 74–75 (2d Cir. 1997). This means that even where the fact of copying is conceded, no legal consequences will follow from that fact unless the copying is substantial. See Laureyssens v. Idea Group, Inc., 964 F.2d 131, 140 (2d Cir. 1992); 4 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright § 13.03[A], at 13-30.2. The principle that trivial copying does not constitute actionable infringement has long been a part of copyright law. Indeed, as [a judge] observed over 80 years ago: “Even where there is some copying, that fact is not conclusive of infringement. Some copying is permitted. In addition to copying, it must be shown that this has been done to an unfair extent.” West Publ’g Co. v. Edward Thompson Co., 169 F. 833, 861 (E.D.N.Y. 1909). This principle reflects the legal maxim, de minimis non curatlex (often rendered as, “the law does not concern itself with trifles”). See Ringgold, 126 F.3d at 74–75.

Newton, 388 F.3d at 1192–93. In other words, to establish its infringement claim, Plaintiff must show that the copying was greater than de minimis.

Plaintiff’s claim encompasses two distinct alleged infringements: infringement of the copyright to the composition of Love Break and infringement of the copyright to the sound recording of Love Break. Compare 17 U.S.C. § 102(a)(2) (protecting “musical works”) with id. § 102(a)(7) (protecting “sound recordings”); see Erickson v. Blake, 839 F.Supp.2d 1132, 1135 n.3 (D. Or. 2012) (“Sound recordings and musical compositions are separate works with their own distinct copyrights.”); see also Newton, 388 F.3d at 1193–94 (noting the distinction). We squarely held in Newton, 388 F.3d at 1193, that the de minimis exception applies to claims of infringement of a copyrighted composition. But it is an open question in this circuit whether the exception applies to claims of infringement of a copyrighted sound recording.

Below, we address (A) whether the alleged copying of the composition or the sound recording was de minimis, (B) whether the de minimis exception applies to alleged infringement of copyrighted sound recordings, and (C) whether the district court abused its discretion in awarding attorney’s fees to Defendants under 17 U.S.C. § 505.6.6

A. Application of the De Minimis Exception

A “use is de minimis only if the average audience would not recognize the appropriation.” Newton, 388 F.3d at 1193; see id. at 1196 (affirming the grant of summary judgment because “an average audience would not discern Newton’s hand as a composer … from Beastie Boys’ use of the sample”); Fisher v. Dees, 794 F.2d 432, 435 n.2 (9th Cir. 1986) (“As a rule, a taking is considered de minimis only if it is so meager and fragmentary that the average audience would not recognize the appropriation.”); see also Dymow v. Bolton, 11 F.2d 690, 692 (2d Cir. 1926) (“[C]opying which is infringement must be something which ordinary observations would cause to be recognized as having been taken from the work of another.” (internal quotation marks omitted)). Accordingly, we must determine whether a reasonable juror could conclude that the average audience would recognize the appropriation. We will consider the composition and the sound recording copyrights in turn.7

1. Alleged Infringement of the Composition Copyright

When considering an infringement claim of a copyrighted musical composition, what matters is not how the musicians actually played the notes but, rather, a “generic rendition of the composition.” Newton, 388 F.3d at 1194; see id. at 1193 (holding that, when considering infringement of the composition copyright, one “must remove from consideration all the elements unique to [the musician’s] performance”). That is, we must compare the written compositions of the two pieces.

Viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to Plaintiff, Defendants copied two distinct passages in the horn part of the score for Love Break. First, Defendants copied the quarter-note single horn hit. But no additional part of the score concerning the single horn hit is the same, because the single horn hit appears at a different place in the measure. In Love Break, the notes for the measure are: half-note rest, quarter-note rest, single horn hit. In Vogue, however, the notes for the measure are: half-note rest, eighth-note rest, single horn hit, eighth-note rest. Second, Defendants copied a full measure that contains the double horn hit. In both songs, the notes for the measure are: half-note rest, eighth-note rest, eighth-note horn hit, quarter-note horn hit. In sum, Defendants copied, at most, a quarter-note single horn hit and a full measure containing rests and a double horn hit.

After listening to the recordings, we conclude that a reasonable jury could not conclude that an average audience would recognize the appropriation of the composition. Our decision in Newton is instructive. That case involved a copyrighted composition of “a piece for flute and voice.” Newton, 388 F.3d at 1191. The defendants used a six-second sample that “consist[ed] of three notes, C—D flat—C, sung over a background C note played on the flute.” Id. The composition also “require[d] overblowing the background C note that is played on the flute.” Id. The defendants repeated a six-second sample “throughout [the song], so that it appears over forty times in various renditions of the song.” Id. at 1192. After listening to the recordings, we affirmed the grant of summary judgment because “an average audience would not discern [the composer’s] hand as a composer.” Id. at 1196.

The snippets of the composition that were (as we must assume) taken here are much smaller than the sample at issue in Newton. The copied elements from the Love Break composition are very short, much shorter than the six-second sample in Newton. The single horn hit lasts less than a quarter-second, and the double horn hit lasts—even counting the rests at the beginning of the measure—less than a second. Similarly, the horn hits appear only five or six times in Vogue, rather than the dozens of times that the sampled material in Newton occurred in the challenged song in that case. Moreover, unlike in Newton, in which the challenged song copied the entire composition of the original work for the given temporal segment, the sampling at issue here involves only one instrument group out of many. As noted above, listening to the audio recordings confirms what the foregoing analysis of the composition strongly suggests: A reasonable jury could not conclude that an average audience would recognize an appropriation of the Love Break composition.

2. Alleged Infringement of the Sound Recording Copyright

When considering a claimed infringement of a copyrighted sound recording, what matters is how the musicians played the notes, that is, how their rendition distinguishes the recording from a generic rendition of the same composition. See Newton, 388 F.3d at 1193 (describing the protected elements of a copyrighted sound recording as “the elements unique to [the musician’s] performance”). Viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to Plaintiff, by accepting its experts’ reports, Pettibone sampled one single horn hit, which occurred at 3:35 in Love Break. Pettibone then used that sampled single horn hit to create the double horn hit used in Vogue.

The horn hit itself was not copied precisely. According to Plaintiff’s expert, the chord “was modified by transposing it upward, cleaning up the attack slightly in order to make it punchier [by truncating the horn hit] and overlaying it with other sounds and effects. One such effect mimicked the reverse cymbal crash…. The reverb/delay ‘tail’ … was prolonged and heightened.” Moreover, as with the composition, the horn hits are not isolated sounds. Many other instruments are playing at the same time in both Love Break and Vogue.

In sum, viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to Plaintiff, Pettibone copied one quarter-note of a four-note chord, lasting 0.23 seconds; he isolated the horns by filtering out the other instruments playing at the same time; he transposed it to a different key; he truncated it; and he added effects and other sounds to the chord itself.8 For the double horn hit, he used the same process, except that he duplicated the single horn hit and shortened one of the duplicates to create the eighth-note chord from the quarter-note chord. Finally, he overlaid the resulting horn hits with sounds from many other instruments to create the song Vogue.

After listening to the audio recordings submitted by the parties, we conclude that a reasonable juror could not conclude that an average audience would recognize the appropriation of the horn hit. That common-sense conclusion is borne out by dry analysis. The horn hit is very short—less than a second. The horn hit occurs only a few times in Vogue. Without careful attention, the horn hits are easy to miss. Moreover, the horn hits in Vogue do not sound identical to the horn hits from Love Break. As noted above, assuming that the sampling occurred, Pettibone truncated the horn hit, transposed it to a different key, and added other sounds and effects to the horn hit itself. The horn hit then was added to Vogue along with many other instrument tracks. Even if one grants the dubious proposition that a listener recognized some similarities between the horn hits in the two songs, it is hard to imagine that he or she would conclude that sampling had occurred.

A quirk in the procedural history of this case is illuminating on this point. Plaintiff’s primary expert originally misidentified the source of the sampled double horn hit. In his original report, the expert concluded that both a single horn hit and a double horn hit were sampled from Love Break. The parties later discovered the original tracks to Vogue and were able to listen to the horn hits without interference from the many other instruments. After listening to those tracks, the expert decided that he had erred in opining that a double horn hit was sampled. He concluded instead that only a single horn hit was sampled, which was used to create the double horn hit in Vogue. In other words, a highly qualified and trained musician listened to the recordings with the express aim of discerning which parts of the song had been copied, and he could not do so accurately. An average audience would not do a better job.

In sum, the district court correctly held that summary judgment to Defendants was appropriate on the issue of de minimis copying.

B. The De Minimis Exception and Sound Recordings

Plaintiff argues, in the alternative, that even if the copying here is trivial, that fact is irrelevant because the de minimis exception does not apply to infringements of copyrighted sound recordings. Plaintiff urges us to follow the Sixth Circuit’s decision in Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films, 410 F.3d 792 (6th Cir. 2005), which adopted a bright-line rule: For copyrighted sound recordings, any unauthorized copying—no matter how trivial—constitutes infringement.

The rule that infringement occurs only when a substantial portion is copied is firmly established in the law. The leading copyright treatise traces the rule to the mid-1800s. 4 Melville B. Nimmer & David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright § 13.03[A][2][a], at 13-56 to 13-57, 13-57 n.102 (2013) (citing Folsom v. Marsh, 9 F.Cas. 342, No. 4901 (C.C. Mass. 1841)); id. § 13.03[E][2], at 13-100 & n.208 (citing Daly v. Palmer, 6 F.Cas. 1132, No. 3,552 (C.C.S.D.N.Y. 1868)); see also Perris v. Hexamer, 99 U.S. 674, 675–76, 25 L.Ed. 308 1878 (stating that a “copyright gives the author or the publisher the exclusive right of multiplying copies of what he has written or printed. It follows that to infringe this right a substantial copy of the whole or of a material part must be produced.”); Dymow, 11 F.2d 690 (applying the rule in 1926). We recognized the rule as early as 1977: “If copying is established, then only does there arise the second issue, that of illicit copying (unlawful appropriation). On that issue the test is the response of the ordinary lay hearer….” Sid & Marty Krofft Television Prods., Inc. v. McDonald’s Corp., 562 F.2d 1157, 1164 (9th Cir. 1977) (alteration and internal quotation marks omitted), superseded in other part by 17 U.S.C. § 504(b); see Fisher, 794 F.2d at 434 n.2 (using the term “de minimis” to describe the concept). The reason for the rule is that the “plaintiff’s legally protected interest [is] the potential financial return from his compositions which derive from the lay public’s approbation of his efforts.” Krofft, 562 F.2d at 1165 (quoting Arnstein v. Porter, 154 F.2d 464, 473 (2d Cir. 1946)). If the public does not recognize the appropriation, then the copier has not benefitted from the original artist’s expressive content. Accordingly, there is no infringement.

Other than Bridgeport and the district courts following that decision, we are aware of no case that has held that the de minimis doctrine does not apply in a copyright infringement case. Instead, courts consistently have applied the rule in all cases alleging copyright infringement. Indeed, we stated in dictum in Newton that the rule “applies throughout the law of copyright, including cases of music sampling.”9 388 F.3d at 1195 (emphasis added).

Plaintiff nevertheless argues that Congress intended to create a special rule for copyrighted sound recordings, eliminating the de minimis exception. We begin our analysis with the statutory text.

Title 17 U.S.C. § 102, titled “Subject matter of copyright: In general,” states, in relevant part:

(a) Copyright protection subsists, in accordance with this title, in original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device. Works of authorship include the following categories:

(1) literary works;

(2) musical works, including any accompanying words;

(3) dramatic works, including any accompanying music;

(4) pantomimes and choreographic works;

(5) pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works;

(6) motion pictures and other audiovisual works;

(7) sound recordings; and

(8) architectural works.

(Emphasis added.) That provision treats sound recordings identically to all other types of protected works; nothing in the text suggests differential treatment, for any purpose, of sound recordings compared to, say, literary works. Similarly, nothing in the neutrally worded statutory definition of “sound recordings” suggests that Congress intended to eliminate the de minimis exception. See id. § 101 (“ ‘Sound recordings’ are works that result from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds, but not including the sounds accompanying a motion picture or other audiovisual work, regardless of the nature of the material objects, such as disks, tapes, or other phonorecords, in which they are embodied.”).

Title 17 U.S.C. § 106, titled “Exclusive rights in copyrighted works,” states:

Subject to sections 107 through 122, the owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following:

(1) to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords;

(2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work;

(3) to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending;

(4) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly;

(5) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly; and

(6) in the case of sound recordings, to perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission.

Again, nothing in that provision suggests differential treatment of de minimis copying of sound recordings compared to, say, sculptures. Although subsection (6) deals exclusively with sound recordings, that subsection concerns public performances; nothing in its text bears on de minimis copying.

Instead, Plaintiff’s statutory argument hinges on the third sentence of 17 U.S.C. § 114(b), which states:10

The exclusive rights of the owner of copyright in a sound recording under clauses (1) and (2) of section 106 do not extend to the making or duplication of another sound recording that consists entirely of an independent fixation of other sounds, even though such sounds imitate or simulate those in the copyrighted sound recording.

Like all the other sentences in § 114(b), the third sentence imposes an express limitation on the rights of a copyright holder: “The exclusive rights of the owner of a copyright in a sound recording … do not extend to the making or duplication of another sound recording [with certain qualities].” Id. (emphasis added); see id. (first sentence: “exclusive rights … do not extend” to certain circumstances; second sentence: “exclusive rights … do not extend” to certain circumstances; fourth sentence: “exclusive rights … do not apply” in certain circumstances). We ordinarily would hesitate to read an implicit expansion of rights into Congress’ statement of an express limitation on rights. Given the considerable background of consistent application of the de minimis exception across centuries of jurisprudence, we are particularly hesitant to read the statutory text as an unstated, implicit elimination of that steadfast rule.

A straightforward reading of the third sentence in § 114(b) reveals Congress’ intended limitation on the rights of a sound recording copyright holder: A new recording that mimics the copyrighted recording is not an infringement, even if the mimicking is very well done, so long as there was no actual copying. That is, if a band played and recorded its own version of Love Break in a way that sounded very similar to the copyrighted recording of Love Break, then there would be no infringement so long as there was no actual copying of the recorded Love Break. But the quoted passage does not speak to the question that we face: whether Congress intended to eliminate the longstanding de minimis exception for sound recordings in all circumstances even where, as here, the new sound recording as a whole sounds nothing like the original.

Even if there were some ambiguity as to congressional intent with respect to § 114(b), the legislative history clearly confirms our analysis on each of the above points. Congress intended § 114 to limit, not to expand, the rights of copyright holders: “The approach of the bill is to set forth the copyright owner’s exclusive rights in broad terms in section 106, and then to provide various limitations, qualifications, or exemptions in the 12 sections that follow. Thus, everything in section 106 is made ‘subject to sections 107 through 118,’ and must be read in conjunction with those provisions.” H.R. Rep. No. 94-1476, at 61 (1976), reprinted in 1976 U.S.C.C.A.N. 5659, 5674.

With respect to § 114(b) specifically, a House Report stated:

Subsection (b) of section 114 makes clear that statutory protection for sound recordings extends only to the particular sounds of which the recording consists, and would not prevent a separate recording of another performance in which those sounds are imitated. Thus, infringement takes place whenever all or any substantial portion of the actual sounds that go to make up a copyrighted sound recording are reproduced in phonorecords by repressing, transcribing, recapturing off the air, or any other method, or by reproducing them in the soundtrack or audio portion of a motion picture or other audiovisual work. Mere imitation of a recorded performance would not constitute a copyright infringement even where one performer deliberately sets out to simulate another’s performance as exactly as possible.

Id. at 106, reprinted in 1976 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 5721 (emphasis added). That passage strongly supports the natural reading of *884 § 114(b), discussed above. Congress intended to make clear that imitation of a recorded performance cannot be infringement so long as no actual copying is done. There is no indication that Congress intended, through § 114(b), to expand the rights of a copyright holder to a sound recording.

Perhaps more importantly, the quoted passage articulates the principle that “infringement takes place whenever all or any substantial portion of the actual sounds … are reproduced.” Id. (emphasis added). That is, when enacting this specific statutory provision, Congress clearly understood that the de minimis exception applies to copyrighted sound recordings, just as it applies to all other copyrighted works. In sum, the statutory text, confirmed by the legislative history, reveals that Congress intended to maintain the de minimis exception for copyrighted sound recordings.

In coming to a different conclusion, the Sixth Circuit reasoned as follows:

[T]he rights of sound recording copyright holders under clauses (1) and (2) of section 106 “do not extend to the making or duplication of another sound recording that consists entirely of an independent fixation of other sounds, even though such sounds imitate or simulate those in the copyrighted sound recording.” 17 U.S.C. § 114(b) (emphasis added). The significance of this provision is amplified by the fact that the Copyright Act of 1976 added the word “entirely” to this language. Compare Sound Recording Act of 1971, Pub. L. 92-140, 85 Stat. 391 (Oct. 15, 1971) (adding subsection (f) to former 17 U.S.C. § 1) (“does not extend to the making or duplication of another sound recording that is an independent fixation of other sounds”). In other words, a sound recording owner has the exclusive right to “sample” his own recording.

Bridgeport, 410 F.3d at 800–01.

We reject that interpretation of § 114(b). Bridgeport ignored the statutory structure and § 114(b)’s express limitation on the rights of a copyright holder. Bridgeport also declined to consider legislative history on the ground that “digital sampling wasn’t being done in 1971.” 410 F.3d at 805. But the state of technology is irrelevant to interpreting Congress’ intent as to statutory structure. Moreover, as Nimmer points out, Bridgeport’s reasoning fails on its own terms because contemporary technology plainly allowed the copying of small portions of a protected sound recording. Nimmer § 13.03[A][2][b], at 13-62 n.114.16.

Close examination of Bridgeport’s interpretive method further exposes its illogic. In effect, Bridgeport inferred from the fact that “exclusive rights … do not extend to the making or duplication of another sound recording that consists entirely of an independent fixation of other sounds,” 17 U.S.C. § 114(b) (emphases added), the conclusion that exclusive rights do extend to the making of another sound recording that does not consist entirely of an independent fixation of other sounds. As pointed out by Nimmer, Bridgeport’s interpretive method “rests on a logical fallacy.” Nimmer § 13.03[A][2][b], at 13-61; see also Saregama India Ltd. v. Mosley, 687 F.Supp.2d 1325, 1340–41 (S.D. Fla. 2009) (critiquing Bridgeport’s interpretive method for a similar reason). A statement that rights do not extend to a particular circumstance does not automatically mean that the rights extend to all other circumstances. In logical terms, it is a fallacy to infer the inverse of a conditional from the conditional. E.g., Joseph G. Brennan, A Handbook of Logic 79–80 (2d ed. 1961).

For example, take as a given the proposition that “if it has rained, then the grass is not dry.” It does not necessarily follow that “if it has not rained, then the grass is dry.” Someone may have watered the lawn, for instance. We cannot infer the second if-then statement from the first. The first if-then statement does not tell us anything about the condition of the grass if it has not rained. Accordingly, even though it is true that, “if the recording consists entirely of independent sounds, then the copyright does not extend to it,” that statement does not necessarily mean that “if the recording does not consist entirely of independent sounds, then the copyright does extend to it.”

The Sixth Circuit also looked beyond the statutory text, to the nature of a sound recording, and reasoned:

[E]ven when a small part of a sound recording is sampled, the part taken is something of value. No further proof of that is necessary than the fact that the producer of the record or the artist on the record intentionally sampled because it would (1) save costs, or (2) add something to the new recording, or (3) both. For the sound recording copyright holder, it is not the “song” but the sounds that are fixed in the medium of his choice. When those sounds are sampled they are taken directly from that fixed medium. It is a physical taking rather than an intellectual one.

Bridgeport, 410 F.3d at 801–02 (footnote omitted).

We disagree for three reasons. First, the possibility of a “physical taking” exists with respect to other kinds of artistic works as well, such as photographs, as to which the usual de minimis rule applies. See, e.g., Sandoval v. New Line Cinema Corp., 147 F.3d 215, 216 (2d Cir. 1998) (affirming summary judgment to the defendant because the defendant’s use of the plaintiff’s photographs in a movie was de minimis). A computer program can, for instance, “sample” a piece of one photograph and insert it into another photograph or work of art. We are aware of no copyright case carving out an exception to the de minimis requirement in that context, and we can think of no principled reason to differentiate one kind of “physical taking” from another. Second, even accepting the premise that sound recordings differ qualitatively from other copyrighted works and therefore could warrant a different infringement rule, that theoretical difference does not mean that Congress actually adopted a different rule. Third, the distinction between a “physical taking” and an “intellectual one,” premised in part on “sav[ing] costs” by not having to hire musicians, does not advance the Sixth Circuit’s view. The Supreme Court has held unequivocally that the Copyright Act protects only the expressive aspects of a copyrighted work, and not the “fruit of the [author’s] labor.” Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 349, 111 S.Ct. 1282, 113 L.Ed.2d 358 (1991). Indeed, the Supreme Court in Feist explained at length why, though that result may seem unfair, protecting only the expressive aspects of a copyrighted work is actually a key part of the design of the copyright laws. Id. at 349–54, 111 S.Ct. 1282 (explaining how “the ‘sweat of the brow’ doctrine flouted basic copyright principles”). Accordingly, all that remains of Bridgeport’s argument is that the second artist has taken some expressive content from the original artist. But that is always true, regardless of the nature of the work, and the de minimis test nevertheless applies. See Nimmer § 13.03[A][2][b], at 13-63 to 13-64 (providing a similar critique of Bridgeport’s physical/intellectual distinction and concluding that it “seems to be built on air”).

Because we conclude that Congress intended to maintain the “de minimis” exception for copyrights to sound recordings, we take the unusual step of creating a circuit split by disagreeing with the Sixth Circuit’s contrary holding in Bridgeport. We do so only after careful reflection because, as we noted in Seven Arts Filmed Entertainment Ltd. v. Content Media Corp., 733 F.3d 1251, 1256 (9th Cir. 2013), “the creation of a circuit split would be particularly troublesome in the realm of copyright. Creating inconsistent rules among the circuits would lead to different levels of protection in different areas of the country, even if the same alleged infringement is occurring nationwide.” (Citation, internal quotations marks, and brackets omitted.) We acknowledge that our decision has consequences. But the goal of avoiding a circuit split cannot override our independent duty to determine congressional intent. Otherwise, we would have no choice but to blindly follow the rule announced by whichever circuit court decided an issue first, even if we were convinced, as we are here, that our sister circuit erred.

Moreover, other considerations suggest that the “troublesome” consequences ordinarily attendant to the creation of a circuit split are diminished here. In declining to create a circuit split in Seven Arts, we noted that “the leading copyright treatise,” Nimmer, agreed with the view of our sister circuits. 733 F.3d at 1255. As to the issue before us, by contrast, Nimmer devotes many pages to explaining why the Sixth Circuit’s opinion is, in no uncertain terms, wrong. Nimmer § 13.03[A][2][b], at 13-59 to 13-66.

Additionally, as a practical matter, a deep split among the federal courts already exists. Since the Sixth Circuit decided Bridgeport, almost every district court not bound by that decision has declined to apply Bridgeport’s rule. See, e.g., Saregama, 687 F.Supp.2d at 1340–41 (rejecting Bridgeport’s rule after analysis); Steward v. West, No. 13-02449, Docket No. 179 at 14 n.8 (C.D. Cal. 2014) (unpublished civil minutes) (“declin[ing] to follow the per se infringment analysis from Bridgeport” because Bridgeport “has been criticized by courts and commentators alike”); Batiste v. Najm, 28 F.Supp.3d 595, 625 (E.D. La. 2014) (noting that, because some courts have declined to apply Bridgeport’s rule, “it is far from clear” that Bridgeport’s rule should apply); Pryor v. Warner/Chappell Music, Inc., No. CV13-04344, 2014 WL 2812309, at *7 n.3 (C.D. Cal. June 20, 2014) (unpublished) (declining to apply Bridgeport’s rule because it has not been adopted by the Ninth Circuit); Zany Toys, LLC v. Pearl Enters., LLC, No. 13-5262, 2014 WL 2168415, at *11 n.7 (D.N.J. May 23, 2014) (unpublished) (stating Bridgeport’s rule without discussion); see also EMI Records Ltd v. Premise Media Corp., No. 601209, 2008 WL 5027245 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Aug. 8, 2008) (unpublished) (expressly rejecting Bridgeport’s analysis). Although we are the first circuit court to follow a different path than Bridgeport’s, we are in well-charted territory.

Plaintiff next argues that, because Congress has not amended the copyright statute in response to Bridgeport, we should conclude that Bridgeport correctly divined congressional intent. We disagree. The Supreme Court has held that congressional inaction in the face of a judicial statutory interpretation, even with respect to the Supreme Court’s own decisions affecting the entire nation, carries almost no weight. See Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275, 292, 121 S.Ct. 1511, 149 L.Ed.2d 517 (2001) (“It is impossible to assert with any degree of assurance that congressional failure to act represents affirmative congressional approval of the Court’s statutory interpretation.” (internal quotation marks omitted)). Here, Congress’ inaction with respect to a decision by one circuit court has even less import, especially considering that many other courts have declined to apply Bridgeport’s rule.

Finally, Plaintiff advances several reasons why Bridgeport’s rule is superior as a matter of policy. For example, the Sixth Circuit opined that its bright-line rule was easy to enforce; that “the market will control the license price and keep it within bounds”; and that “sampling is never accidental” and is therefore easy to avoid. Bridgeport, 410 F.3d at 801. Those arguments are for a legislature, not a court. They speak to what Congress could decide; they do not inform what Congress actually decided.11

We hold that the “de minimis” exception applies to actions alleging infringement of a copyright to sound recordings.

C. Attorney’s Fees

Finally, we consider the district court’s award of attorney’s fees to Defendants. The Copyright Act permits a court to “award a reasonable attorney’s fee to the prevailing party.” 17 U.S.C. § 505. “[A]ttorney’s fees are to be awarded to prevailing parties only as a matter of the court’s discretion.” Fogerty v. Fantasy, Inc., 510 U.S. 517, 534, 114 S.Ct. 1023, 127 L.Ed.2d 455 (1994). “In deciding whether to award fees under the Copyright Act, the district court should consider, among other things: the degree of success obtained on the claim; frivolousness; motivation; objective reasonableness of factual and legal arguments; and need for compensation and deterrence.” Maljack Prods., Inc. v. GoodTimes Home Video Corp., 81 F.3d 881, 889 (9th Cir. 1996).

Here, the district court concluded that Plaintiff’s legal claim premised on Bridgeport was objectively unreasonable because, in the court’s view, Plaintiff should have been aware of the critiques of Bridgeport and should have declined to bring the claim. In relying on that reasoning, the court erred as a matter of law. It plainly is reasonable to bring a claim founded on the only circuit-court precedent to have considered the legal issue, whether or not our circuit ultimately agrees with that precedent.

The district court also ruled that Plaintiff’s claim was objectively unreasonable because of issues that hinged on “disputed facts and credibility determinations.” Again, the court erred as a matter of law. If a plaintiff has a claim that hinges on disputed facts sufficient to reach a jury, that claim necessarily is reasonable because a jury might decide the case in the plaintiff’s favor.

Because the district court erred in finding that Plaintiff’s claim was objectively unreasonable, we vacate the award of fees and remand for reconsideration.

Judgment AFFIRMED; award of fees VACATED and REMANDED for reconsideration. The parties shall bear their own costs on appeal.

|

Footnotes

|

|

|

1

|

Plaintiff prefers the label “horn part,” but the label has no effect on the legal analysis. For simplicity, we follow the district court’s convention.

|

|

2

|

The label “instrumental” is misleading: The recording contains many vocals. But again we adopt the terminology used by the district court.

|

|

3

|

In musical terms, assuming that the composition was copied, Pettibone “transposed” the horn hit in Love Break by one-half step, resulting in notes that are half a step higher in Vogue.

|

|

4

|

The record does not appear to disclose the meaning of a “breakdown” version of the horn hit, and neither party attributes any significance to this form of the horn hit.

|

|

5

|

For example, Plaintiff hired Shimkin and then brought this action, raising doubts about Shimkin’s credibility; Pettibone and others testified that Shimkin was not present during the creation of Vogue and was not even employed by Pettibone at that time; and Defendants’ experts dispute the analysis and conclusions of Plaintiff’s experts.

|

|

6

|

Because we affirm the judgment on the ground that any copying was de minimis, we do not reach Defendants’ alternative arguments. Accordingly, we assume without deciding that the horn hits are “original.” See Newton, 388 F.3d at 1192 (assuming originality). We also assume without deciding that Pettibone is not a co-owner of Love Break.

|

|

7

|

It appears that Plaintiff did not introduce into the summary judgment record a copy of the copyrighted composition and did not introduce a copy of one of the two allegedly infringing sound recordings. We need not decide whether those omissions are fatal to Plaintiff’s claims. For purposes of our analysis, we accept the partial transcription of the composition by Plaintiff’s expert, and we analyze the sound recordings that Plaintiff did submit.

|

|

8

|

For all of those reasons, we decline to apply the “fragmented literal similarity” test: Defendants did not copy “a portion of the plaintiff’s work exactly or nearly exactly.” Newton, 388 F.3d at 1195; see also Dr. Seuss Enters., L.P. v. Penguin Books USA, Inc., 109 F.3d 1394, 1398 n.4 (9th Cir. 1997) (rejecting the category of “fragmented literal similarity”).

|

|

9

|

Defendants incorrectly assert that the quoted sentence controls the outcome in this case. Newton considered an alleged infringement of the composition only; it had no occasion to consider—and did not consider—the argument that a different rule applies to the infringement of sound recordings.

|

|

10

|

The full subsection states:

17 U.S.C. § 114(b). Nothing in the other sentences advances Plaintiff’s argument.

|

|

11

|

It also is not clear that the cited policy reasons are necessarily persuasive. For example, this particular case presents an example in which there is uncertainty as to enforcement—musical experts disagree as to whether sampling occurred. As another example, it is not necessarily true that the market will keep license prices “within bounds”—it is possible that a bright-line rule against sampling would unduly stifle creativity in certain segments of the music industry because the licensing costs would be too expensive for the amateur musician. In any event, even raising these counter-points demonstrates that the arguments, as Plaintiff concedes, rest on policy considerations, not on statutory interpretation. One cannot answer questions such as how much licensing cost is too much without exercising value judgments—matters generally assigned to the legislature.

|