New Technology

This discussion considers the potential of music notation software to provide more efficient and effective methods of establishing or disproving similarities between musical works than those that have been used until now in music copyright infringement litigation. Most of the techniques offered here of manipulating musical data have been anticipated by musicians who have testified in music copyright cases with cumbersome diagrams, audiotapes, and perhaps even an instrument (the first appearance of which must inevitably spark a frisson of delight among those in the courtroom – dozing jurors particularly). The efficiency, however, with which one can carry out these musical manipulations using notation software, the excellent audio and graphic renditions it produces, and the ease of dissemination of graphic and audio files associated with digital scores, are among the advantages of applying this relatively new technology to this intersection of music and law.

This discussion considers first the applications of notation software and the use of the software itself to demonstrate the similarities or differences between two or more musical works. Second, we consider use of search engines to retrieve prior art from thematic or full score collections of digital music data. Our objective is not to attempt an exhaustive treatment of the applications of these technologies, but rather to provoke readers to experiment with them, or at least to reflect upon their potential efficacy in this area. The discussion poses a number of questions that readers might entertain in developing an understanding of this subject.

Notation Software and Determination of Melodic Similarity

In Hein v. Harris (1923) the defendant attempted to persuade the court that prior art songs were similar enough to plaintiff’s “Arab Love Song” for the court to conclude that in writing his song the plaintiff had simply borrowed existing generic musical conventions without adding sufficient original expression on which to stake an independent claim of copyright.

Learned Hand, who wrote the Hein opinion, appears to have taken defendant’s prior art defense seriously. One finds in the docket, on a copy of the sheet music of the so-called prior art, Hand’s meticulous annotations marking the common pitches among these numbers. Holding for the plaintiff, however, Hand found that the similarities among the prior art works and the plaintiff’s extended only to generic stylistic features, and that defendant’s melody was much more similar to plaintiff’s than were those of any of the alleged prior art songs.

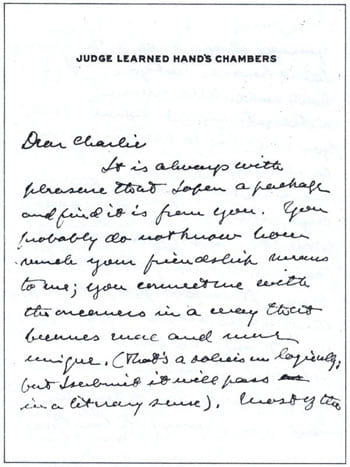

Here is a sample of Learned Hand’s handwriting used to confirm that it was Hand who marked up the sheet music offered by the defendant, and found in the case docket.

This handwriting sample is from a letter Learned Hand wrote on Christmas Eve, 1939 to Charles E. Wyzanski, who was the first law clerk of Learned’s cousin Augustus Hand, and who was about to become a judge himself. It is taken from a reproduction of the letter in The Remarkable Hands: An Affectionate Portrait, edited by Marcia Nelson, and published in New York in 1983 by the Foundation of the Federal Bar Council.

Charles Brown’s “Mobile Prance” – published by defendant Harris himself – was one of the numbers offered to the court as prior art evidence. This is a page of the copy that Hand marked up (taken from the case docket); the tidy hatch marks over certain notes are in keeping with the emphasis Hand placed in this, and similar cases, on the precise number of pitch concurrences between disputed works as highly probative on the questions of similarity and copying.

If Learned Hand were trying this case today how likely would it be that he would still hold for the plaintiff? Below we consider how the parties in Hein v. Harris might have used music notation software to support their respective positions. The reader might consider the question whether, on balance, use of music digital technology makes infringement more or less discernible, and more specifically the likelihood that music evidence in digital form might have affected Hand’s decision in this case.

Plaintiffs could point up similarities between musical works using notation software to normalize melodies that at first blush might appear unrelated to non-musicians. Using programs like Finale one can, for instance, with the proverbial “click of the mouse,” transpose melodies in disparate keys to a single key; give a uniform tempo and instrumentation to the MIDI playbacks of these melodies; assign a single meter to works that have different meters; and transpose lines from less commonly read clefs into G and F clefs. Because digitized music evidence is unfettered by the coils of physicality and place judges could thoughtfully review and manipulate this evidence in the privacy of their offices, as could jurors in their jury room.

If I were to testify on behalf of the plaintiff in Hein v. Harris I must try to convince the court that the defendant took an economically valuable part of plaintiff’s work. I would try to minimize the significance – economic or musical – of the differences between these parts. Because disputed musical works in these cases are never identical I will need to “normalize” their melodies in order to compare them meaningfully. I might transpose both melodies to a common key, program the MIDI files to perform both works at the same tempo, at the same volume and with similar attack and with the same instrumentation. I might drop or add upbeats, change enharmonic spellings and flatten syncopated rhythms. These ministrations accomplished, superimposing the defending melody over the plaintiff’s might help indicate how the essential musical expression of the latter work is derived from the former.

Here are the disputed themes from Hein v. Harris in their original form:

To normalize the defending theme let us transpose it to E-flat and adjust its syncopated rhythm a bit.

After having so tinkered with the melody, when one superimposes it over plaintiff’s one sees and hears relatively few dissonances, or even divergences. Moreover, if one sets this slightly doctored melody over the unaltered accompaniment of the plaintiff’s theme, one finds a felicitous correspondence between them.

Finally, one finds a telling coherence to a new theme derived from every other measure of the disputed themes, set over the plaintiff’s accompaniment (and, one notes that none of the prior art melodies that defendant cites are tractable to such contortion).

Even without these bits of arguably contrived evidence supporting the plaintiff’s position one must concede a family resemblance between the themes based on their sharing a duple meter, light syncopation, and a strutting opening motive rising by step. To counter inferences of substantial similarity that one might draw from the similar melodic and harmonic scansions of the songs, the defendant will need to emphasize not only the number of differences between the melodies, but also the significance of these differences to the overall sound of performances of the two works.

The defendant could, for instance, simply superimpose his melody over plaintiff’s, without making any adjustments to either, to underscore the differences between them.

One wonders, however, whether the resulting notational gibberish and aural cacophony of the MIDI rendering would have probative value on the question of melodic similarity regardless of the extent to which musically uneducated jurors and judges might be impressed by such testimony.

The question of the defendant’s testimony raises again the issue of normalization of the allegedly misappropriated thematic material. One considers certain pitches of a melody to be more important than others based on a variety of factors, e.g. place in measure, key, duration, meter and genre of work. As discussed, in order to make a dramatic showing of musical similarities between “Arab Love Song” and “Woodpecker” (in the form of highly similar notation and audio files) the plaintiff must adjust several features of the defendant’s theme. The defendant might argue, therefore, that plaintiff’s normalization of defendant’s theme not only stripped away the very elements that made the defendant’s work original and viable as an independently copyrightable work, but also that if one performed similar ministrations on the plaintiff’s theme one might reduce it to a mere collection of generic conventions associated with ragtime.

Prior Art Defense

In Hein v. Harris the defendant used an “even if” argument along these lines: even if his song were substantially similar to the plaintiff’s, the elements shared between the works were commonplaces that are found in earlier works of this genre. Like the plaintiff who would normalize defendant’s melody to underscore its similarities to his, the defendant would similarly need to normalize plaintiff’s theme to underscore its similarity to works preceding it. The more information that the defendant strips from the plaintiff’s theme to make a plausible case for a prior art claim, however, the greater the inference that the plaintiff’s number is in fact original.

The defendant offered four popular songs to support his prior art argument.

This evidence did not impress the court; of the four numbers that the defendant put forth Learned Hand found only “Bon Bon Buddy” to be similar to “Arab Love Song,” and thought the similarity too brief to support the defendant’s claim of derivation.

To identify the four prior art works, the defendant’s music expert relied upon his familiarity with the popular song repertory of his era. One wonders whether his prior art testimony would have been more persuasive if he had had access to a searchable database of the themes or scores of all popular numbers in America from 1880 to 1910. This database does not yet exist, but publishers’ and archivists’ adoption of digital notation technology points to a time when it will.

Like digital text, digital music notation is tractable to indexing and searching. Using queries of note names, interval sequences, and rough and refined melodic contours, one can search data collections of complete scores or indexes of themes. Digital notation searching technology is young and developers ponder questions of how to massage queries and searchable data so as to improve their elasticity for octave placement and enharmonic spellings, while accommodating more information about rhythm. (Digital music audio file searching offers different, but equally nettlesome problems.) One of the most extensive digital theme indexes to date is Themefinder , a project of Stanford’s Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities. Themefinder is a searchable collection of over 35,000 themes of Folksongs, Classical, and Renaissance works.

Melodic profiles are influenced by various factors, including the genre of a work, and whether the melody is modal or tonal, instrumental or vocal. Themefinder’s repertories are inapposite to those encompassing the popular works of music copyright cases. One might then, best explore the potential usefulness of resources like Themefinder in plagiarism disputes using a melody with Classic characteristics.

In 1794, Beethoven’s tuition with Franz Josef Haydn (“Papa” Haydn – a curious sobriquet given that he had no children) ended with misgivings on the part of both composers. Let’s assume that Beethoven wrote a piano trio in 1796, the third movement of which, opens with the following theme:

Does this look and sound familiar? Haydn might have thought so given the opening of the elegant and playful Menuet from his “London” Symphony, first performed in the city in 1795:

Accused of plagiarism (a not uncommon accusation lobbed among 18th and 19th century composers, although usually without the gruesome legal and economic baggage that attends these charges today), Beethoven might have claimed that both his and Haydn’s themes were derived from prior art, as indicated by information obtained from Themefinder. First, as indicated in the example above, both melodies are reduced to strings of searchable information. Searching Themefinder using a query of the first five pitches of Haydn’s theme retrieves Haydn’s work, a Schubert symphony (not, of course, prior art) and sixteen other works: Link to Themefinder Results

Something to ponder… |

|---|

|

What should one make of these results? Leaving aside the question how closely Haydn’s theme maps any one of the folk tunes, is the fact that our search results contain a preponderance of music with no individual attribution (i.e. echt public domain material in the form of folk melodies) useful to either party in this dispute? If you were deciding this case would your decision be affected by the Themefinder results? In your decision, which party should prevail, and to what extent would your ruling be influenced by musical analysis of the works versus the undisputed close personal contact between the litigants? |

Melodic Analysis and Popular Music after 1960

Leaving behind the Tin Pan Alley era of Hein v. Harris (1923), let us consider whether digital notation software and related MIDI technology might have greater, lesser or similar probative value for determining similarity in music infringement cases involving popular music from the 1960s on.

For this exercise, let us use the manipulative digital notation and MIDI files of song excerpts from the Bee Gees and Fogerty cases (1984 and 1994 respectively).

Ronald Selle, “Let it End” View Video Clip

Gibb Brothers, “How Deep is Your Love” View Video Clip

John Fogerty, “Run Through the Jungle” View Video Clip

John Fogerty, “The Old Man Down the Road” View Video Clip

It was rumored that Fantasy Records sued John Fogerty for infringement after relations soured on other grounds between the record company and this performer. But the court did not dismiss the case out of hand; what did Fantasy personnel hear between “Run Through the Jungle” and “The Old Man Down the Road” that excited them to pursue this protracted litigation? Having juxtaposed the melodies of the digital music files associated with this case (above) it is worth considering the significance of Fogerty’s performance style despite the fact that the case was ostensibly about infringement of music.

Something to ponder… |

|---|

|

Is it likely that Fantasy Records would have brought an infringement suit against a singer other than Fogerty who had written and recorded “Old Man”? Or, for that matter, would Fogerty (assuming he had a valid copyright interest in “Jungle”) have claimed infringement if another singer wrote and recorded “Old Man”? If not, was Fantasy’s claim against Fogerty specious, or could it be that, in fact, the economic value in Fogerty’s songs lies not in their music per se, but rather apart from those musical components that can be reduced to graphic representation (scores), and that Fogerty’s later song derives most of its economic value from something less tractable to symbolic representation? |

Let us turn to the Bee Gees for a moment. During their infringement trial the plaintiff’s attorney played a recording of a performance of the melody of plaintiff’s number “Let It End” for Maurice Gibb, who was under oath. Maurice Gibb erroneously identified this music as taken from the Bee Gees’ song, and the plaintiff rested his case. (One wonders how warmly the other Gibbs received their brother Maurice back at the hotel that evening…) The slip must have impressed the jury, who found the Bee Gees liable for infringement, although the judge ultimately disregarded their verdict. Juxtaposition and manipulation of the two melodies contained in the digital files linked above suggest Maurice Gibb’s error was less egregious than one might imagine; the melodies are clearly similar.

Something to ponder… |

|---|

|

If the raw musical material of Ronald Selle’s “Let It End” was strikingly similar to the Bee Gees’ later hit, why did Selle’s song never make it out of the garage while the Bee Gees’ number delighted millions of teenagers worldwide? Does it all boil down to marketing and the purportedly craven business practices of major record companies as commonly claimed by not-so-photogenic pop star wannabes? Or, are there other factors that more powerfully affect the success of a rock number than its musical essence as distilled in the notated skeletons on which music plagiarism cases turn? What are these attributes of successful popular numbers, and should they be protected as a form of property, and by copyright? If, as implied here, non-musical aspects of popular songs today, and their performances in particular, are more important to their commercial success than musical elements, how does one explain the fact that usually one or two numbers on a popular album may be wildly popular while the others languish in obscurity and are skipped over, if possible, by those listening to the album? Can you conjure a mental image of the physiognomies of Cole Porter (Arnstein v. Porter), Jerome Kern (Fisher v. Dillingham) or Jeri Sullivan (Baron v. Feist)? Perhaps not, but what about those of Ella Fitzgerald, Fred Astaire or the Andrew Sisters, who performed and recorded these songwriters’ numbers? And what about images of the Bee Gees, John Fogerty, Michael Jackson or the Beatles? — even if one never willingly listens to their songs, one knows what these songwriter/performers look like. Is that only due to the fact that their popularity was more recent than that of Porter and Kern, and happened in an era saturated with television and other cultural atrocities like “music videos”? Or does this also reflect changes since the middle of the 20th century in the ways popular music is created, performed, marketed and consumed? Along these lines, consider the fact that in the first half of the 20th century sheet music publishing and piano manufacturing were vibrant industries in the U.S. What significance should one ascribe to the remarkable constriction of these industries in the latter half of the 20th century, and to the woeful state of formal education in music, to the ways popular music is now produced and consumed? |

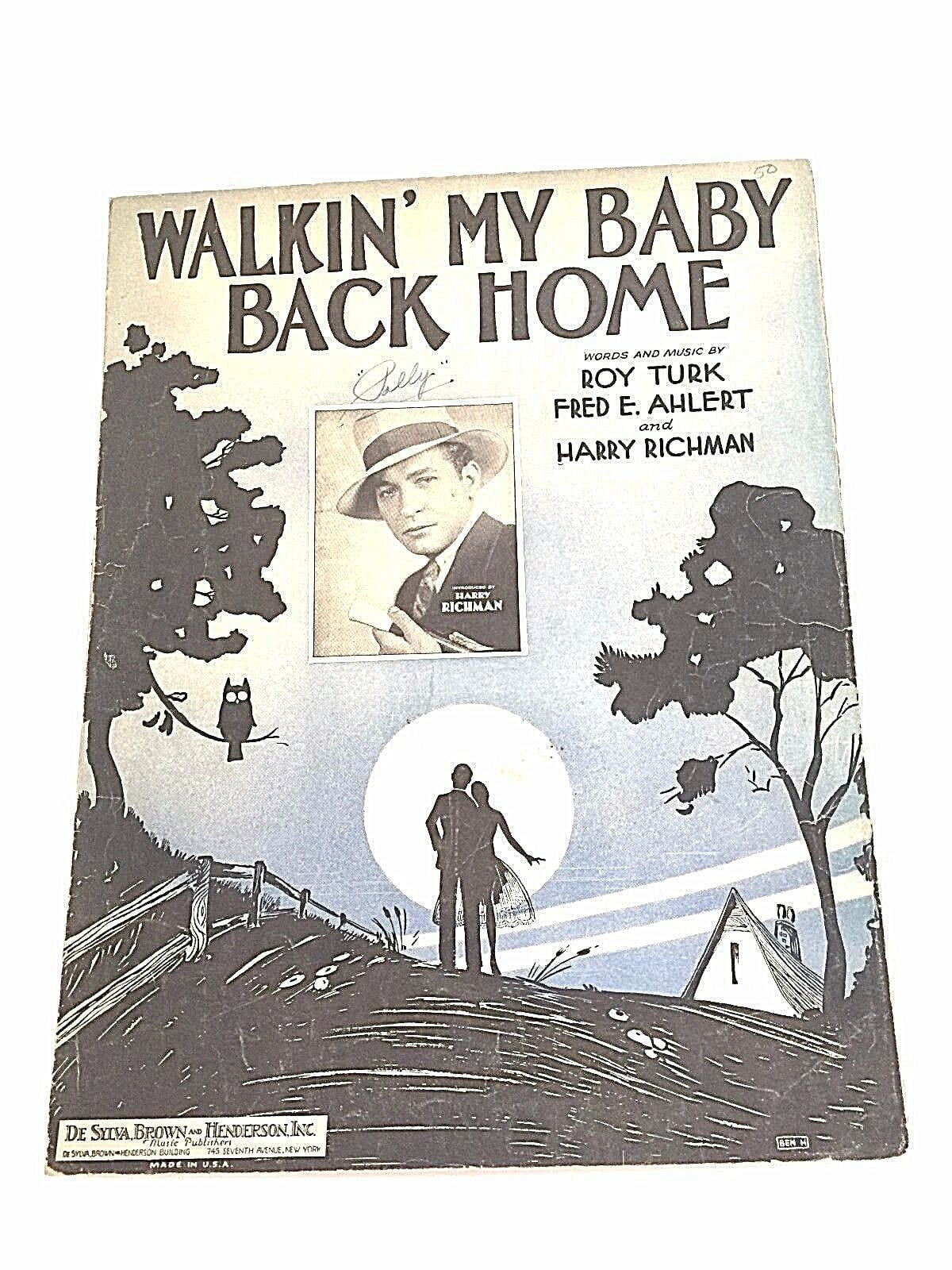

The cover art of sheet music published in the early decades of the 20th Century typically features a fanciful drawing of a scene related to the subject matter of the song, sometimes with an inset photograph of the songwriter or performer.

Front Cover of the Sheet Music “Walkin’ My Baby Back Home” from 1930

Let us compare this image to the non-musical information one commonly finds in sheet music publications of rock songs. In John Fogerty’s song collection “Centerfield” (that contains “The Old Man Down the Road”, the number at issue in Fantasy v. Fogerty) one finds five photographs of Fogerty — three in full-page color glossies no less; drawings and photos of gimcrackery one associates with clichéd images of a wholesome 1950s American boyhood that Fogerty wants consumers to associate with him (baseball caps, a little radio, a penknife, figurines of ballplayers, cowboys and Indians, a baseball glove); and finally a four-page transcript of an “interview” with Fogerty to resonate with the narcissistic hokum of Fogerty’s lyrics directed at what was at the time the work was promoted a large and profitable market of mid-brow white American men born in the 50s and 60s:

[M]y country was the Grand Canyon, Niagara Falls, Montana,

Elvis, Chicago blues and Patrick Henry…”…A-’roundin’ third and headed for home

It’s a brown-eyed handsome man

Anyone can understand the way I feel…

Something to ponder… |

|---|

|

What were Fogerty and his publishers selling, and is this product overall any different from what songwriters and publishers were selling in Tin Pan Alley’s heyday in the 1920s and 30s? In other words, have changes in the creation, performance, marketing and consumption of popular music since the 1920s and 30s affected the locus of commercial value in these works? If so, where has the shift occurred, and how should this shift in value away from purely musical elements bear on the equitable resolution of music copyright infringement claims? Will digital music notation software and searchable graphic and audio theme databases be useful, or increasingly irrelevant in these determinations? If, as copyright minimalists hope and predict, the mercurial nature of digital renderings of works (popular songs in particular) signals a new era in the music industry and the decline or even demise of major record labels, how might these changes play out in the area of music copyright infringement? In a restructured, decentralized music industry should one anticipate a greater or lesser number of infringement suits than under the current regime? |