BGH [Federal Court of Justice] Nov. 3, 1967, Ib ZR 123/65 (Germany)

Disputed Work |

|

“Schwarzbraun ist die Haselnuss” (19th Century Public Domain German Folksong) Music sheet of melody, chords and words Arrangement by Franz Josef Breuer |

Comment by Leonie Schwannecke

- Historical Background

When looking at this case, it should be noted that the folksong “Schwarzbraun ist die Haselnuss” is perceived controversially in Germany. It has first been sung in the 19th century and was well known during the 20th century. With its 4/4 rhythm, it could be used for marching and was adopted and used by the Nazis. For example, it had been printed in a songbook for the Hitler Youth as well as other songbooks for soldiers. Until today, it is thus perceived as a “Nazi-Song” by some. At the same time, the song was rediscovered in the 1950s, when the arrangement in question was also written, and continues to be popular despite its background (for further information (in German) see Nagel, Georg: Schwarzbraun ist die Haselnuss, https://www.lieder-archiv.de/schwarzbraun_ist_die_haselnuss-notenblatt_300393.html, last visited 02/23/2021).

- Case Abstract

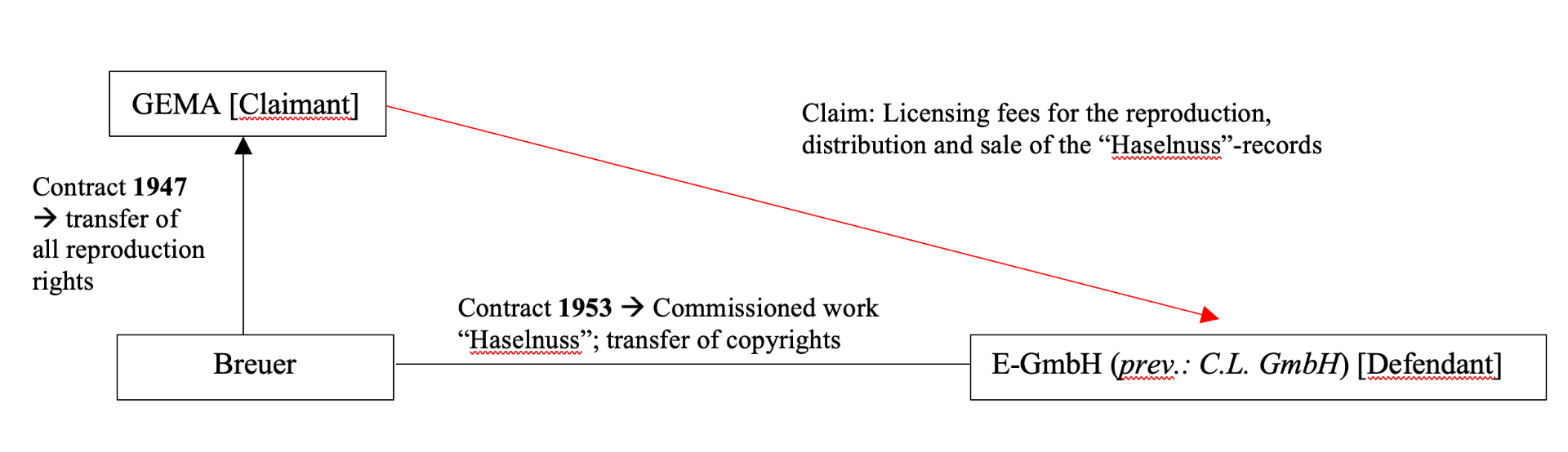

The claimant in this case is the German Society for musical performance and mechanical reproduction rights, GEMA. In 1947, it concluded a contract with the composer Franz Josef Breuer (name redacted in the decision), in which Breuer transferred his mechanical reproduction rights to GEMA. In 1953, Breuer arranged the German folk song “Schwarzbraun ist die Haselnuss” for wind orchestra and men’s choir as a commissioned work for the defendant’s legal predecessor, the C. L. GmbH, to which he assigned his copyright.

The defendant E-GmbH (E) produces, distributes and sells vinyl records, including the record containing Breuer’s arrangement. E registered its recording of “Haselnuss” with GEMA but did not declare Breuer as the arranger. GEMA discovered this and subsequently, in November 1954, informed the defendant that the record was subject to licensing fees due to the contract concluded between GEMA and Breuer in 1947. GEMA’s efforts to recover the licensing fees it deemed to be payable were fruitless and in 1961, GEMA filed a claim seeking the following:

(1) An order against the defendant to refrain from reproducing, distributing or selling the records and tapes with Breuer’s arrangement;

(2) An order against the defendant to disclose the number of records and tapes produced, distributed or leased;

(3) A declaration that the defendant is obligated to compensate the claimant in full for all losses suffered due to the unauthorized reproduction, distribution and lease of the records and tapes.

The defendant, meanwhile, considered the lawsuit to be inadmissible, arguing that GEMA lacked standing for the claims. It averred that the lawsuit was unjustified, arguing that the 1949-contract between GEMA and Breuer did not extend to future rights, and that even if it did, the arrangement in question would not be included among them as it did not constitute a protected work under the German Act on Copyright and Relates Rights because it was not an original creation. Moreover, it claimed that even if the arrangement were protectable, the named defendant, E, could not be held liable: in this event, E would itself have a claim in damages against Breuer. Due to the trusteeship between him and GEMA, E alleged that it could also hold this claim against GEMA.

The Federal Court of Justice in Karlsruhe (BGH) held in favor of GEMA on all three points. In a first step, it clarified that GEMA had standing for the claim as, subject to the arrangement being an original creation and thus protected work, to which it held the rights due to the 1949-contract. Second, the BGH set out the abstract criteria for what constitutes a “Work” – that is, a protected work – in distinction to one of mere “mechanical” editing. At the time of the decision (1965), the German Act on Copyright and Related Rights of 1965 (“Copyright Act”) had just entered into force, replacing the Act on Protected Works in Literature and Musical Art from 1901, thus giving the BGH an opportunity to deal with the differences between the two acts and the question of whether the requirements for what constitutes a protected work had changed.

Third, the BGH applied the criteria set out in step two to Breuer’s work, taking into consideration two divergent expert opinions. The BGH found that Breuer’s arrangement showed sufficient signs of original creation to constitute a protected work under the Copyright Act. Consequently, the defendant was held liable in damages and ordered to refrain from further reproducing, distributing or selling the records and tapes with Breuer’s arrangement.

- Commentary

The following commentary will focus on the question of whether Breuer’s arrangement is an original creation and thus constitutes a work protected by the Copyright Act, rather than by the various licensing agreements relevant to this case.

- Legal Framework

The legal starting point for the question of whether Breuer’s arrangement is protected is § 3 of the Copyright Act, which states:

Translations and other adaptations of a work which are the adapter’s own intellectual creations are protected as independent works without prejudice to the copyright in the adapted work. The insubstantial adaptation of an unprotected musical work is not protected as an independent work.

“Schwarzbraun ist die Haselnuss” is (and was at the time of the arrangement) a folk song in the public domain, and thus not protected as an independent work. Accordingly, Breuer’s arrangement can only be protected under the Copyright Act if it constitutes a substantial adaptation of the original melody, as follows from the second sentence of § 3 of the Copyright Act. This is not the case, if the adaptation is merely a mechanical one, such as the mere transposition of a piece into a different key or a modulation from major to minor, where the basic harmonic, rhythmic and melodic structure stays the same (BeckOK UrhR/Ahlberg § 3 Rn. 21; Schricker/Loewenheim/Loewenheim UrhG § 3 Rn. 29).

- The BGH’s view on the arrangement as an original creation and substantial adaptation

From page 12 to 15, the BGH sets out some abstract criteria on which a work is to be evaluated for protection eligibility under the Copyright Act. Its starting point is a broad interpretation of the term “protected works”. The court stresses that the requirements which need to be met for a work to be protected cannot be set too high. As had already been established under the Act on Protected Works in Literature and Musical Art from 1901, whether a work is protected does not depend on its artistic importance. The BGH clarifies that this standard has not changed with the adoption of the 1965 Copyright Act. Consequently, arrangements made for the purposes of entertainment music, despite often requiring low artistic effort, can generally be protected under § 3 of the Copyright Act. Nevertheless, even these arrangements, require some original creation to meet the threshold of the requirement of the second sentence, namely the substantial adaptation. As it is in the nature of an arrangement that the melody of the edited original work is recognizable, perhaps even identical, this creativity can only be shown through other methods of musical variation.

The BGH found that in choosing the particular instrumentation for his arrangement, and a “sharper” rhythm that leads to stronger impulse on each note, Breuer thereby changed the character of the piece. According to the BGH (and earlier the lower court) these choices may have contributed significantly to the economic success of the sound recording.

- Evaluation

In my opinion, the BGH decided correctly in considering Breuer’s arrangement to be sufficiently original and substantial to be protected under the Copyright Act.

When listening to the underlying folksong melody, and subsequently to the arrangement, notable changes already can be heard in the very beginning of the arrangement. Breuer’s arrangement is introduced by a brief prelude played only by the wind orchestra. The chorus then starts by singing down and then up a minor third on “Schwarz-braun ist”, then up a fourth on “die”, rather than just singing up a fourth on “Schwarz-braun” and repeating that same note as does the original melody. Similar minor changes to the melody can be found throughout the piece. For example, in the second part of the verse, in the original melody, the syllables “ha-ha-ha” repeat the same note; in Breuer’s arrangement the leading voice sings these syllables using a broken triad.

The rhythm of the underlying melody, too, has been altered: whereas the original melody simply uses two quarter notes in the first bar, Breuer replaces them with a dotted quarter-eighth-note combination which is kept throughout the piece. This is what the court described as a “sharpened” rhythm. Also notable is the added interlude between the first and second verse, partly sung by chorus, partly played by the orchestra. In this part particularly, Breuer genuinely “plays” with the original melody and does not simply edit it mechanically. This is especially true given that the original melody does not contain any sort of interlude.

As the BGH sets out, the threshold of originality for a work to be protected under the Copyright Act cannot be too high. This issue brings into question the originality of arrangements that simplify difficult or complex works for the not-so-experienced player, such as youth/children orchestra arrangements of symphonies or film music. (c.f. BeckOK UrhR/Ahlberg29 § 3 Rn. 20 – generally protected). Not protecting such works would constitute hardship, especially considering that many such arrangements evince considerable musical invention. Likewise, not protecting an arrangement that recasts a basic, well-known melody to be played by a specific group – in this case wind orchestra and men’s choir – would be contradictory, even if it does not signify significant artistic effort. As discussed, Breuer does not simply modulate the key of the piece as a “musical mechanic”, but went beyond that through the several harmonic changes occurring throughout the arrangement. These need to be considered in the holistic manner in which they change the basic harmonic, rhythmic and melodic structure of the piece (c.f. BeckOK UrhR/Ahlberg29 § 3 Rn. 22: “The combination of several by themselves unprotected elements can be new and peculiar.”). This approach is not impaired by the fact that the original melody itself is clearly recognizable throughout the arrangement, as is the case here – and as set out by the BGH – which is inherent in an arrangement. Thus, Breuer’s arrangement is not an unsubstantial adaptation of “Schwarzbraun ist die Haselnuss” and consequently protected according to § 3 of the Copyright Act.

—–

German Federal Court of Justice (German) (1967): PDF